This article was originally printed on the fantastic oxfordstudent.com.

Much has been published criticising the phenomenon of ‘voluntourism’, whereby individuals (often students) mix foreign holidays with voluntary work for NGOs.

With social media littered with images of westerners hugging young African children, it is easy to appreciate why critics accuse voluntourism of trivialising poverty, treating it as a spectacle, rather than a complex issue that needs to be treated seriously. Often, as J.K. Rowling lambasted in a series of tweets in 2016, voluntary projects seem to be more about providing CV enhancing experiences for volunteers than about improving the lives of the supposed benefactors. More fundamentally though, there’s the danger that reliance by charities on overseas volunteering can in fact thwart long run development. Volunteers can displace locals from potential jobs, and in doing so prevent skills development within communities, potentially harming project sustainability. For instance, using volunteers to install a bore hole pump is likely inferior to a charity enlisting and enabling locals to build it themselves. Training locals instead of volunteers creates locally based knowledge and avoids the cultivation of a dependency culture.

Criticism has been particularly focused on the many projects that see Westerners volunteer in orphanages. There is consensus amongst experts (such as the Better Care Network, UNICEF and Save the Children) that the orphanage model of child care for vulnerable children can actually cause more harm than good, with institutionalisation undermining the development of social skills and failing to set children up for adulthood. Children in orphanages lack the individual attention and miss out on everyday experiences that are part and parcel of living with a family. Despite this, a 2011 UNICEF report on Cambodia suggested that despite falling numbers of orphans, worringly, the amount of residential institutions has increased. Underlying this is a rise in children with living parents being placed in care; a study by Kevin Browne estimates that 4 out of 5 children placed in institutional care worldwide have at least one living parent. Attracted by the lucrative business opportunity of Westerners paying to ‘help’ these children, developing world orphanages have been guilty of pressurising impoverished parents to place their children in care. Thus while Save the Children’s 2009 report on childcare worldwide concluded that institutional care should be viewed as a last resort, voluntourism in Cambodia was cited in UNICEF’s studies as perpetuating this dangerous model. Voluntourism also serves to worsen problems within orphanages, with the coming and going of volunteers increasing feelings of abandonment.

Bad press for overseas volunteering seems to be feeding into the student attitudes at Oxford. Oxford Development Abroad, a society founded in 2002 which organises volunteering work abroad for Oxford students has seen a marked decline in applications for its projects in recent years. I feel this is a shame. Whilst the criticisms propounded in the media have validity, they don’t apply universally. If steps are taken to ensure projects are responsibly designed and managed, voluntary services can be hugely beneficial to recipient communities. As students, we are more likely to be endowed with time and skills than disposable income, and so are legitimately drawn to volunteering versus purely donating money. It also remains the case that volunteering abroad can give greater perspective on the challenges that the developing world faces. This is particularly relevant to Oxford students, many of whom will find themselves in influential positions in later life, able to affect the deeper systemic change required to tackle poverty at its roots.

The question is, therefore, how to find responsible volunteering projects. A number of organisations such as the International Ecotourism Society and Comhladh in Ireland, have published codes of best practice for NGOs using volunteers. Would-be volunteers should seek out organisations that fulfil these criteria: NGOs should only involve volunteers in projects that have been requested by recipient communities. This makes it more likely that a community will engage with the work of an NGO, promoting sustainability. Responsible NGOs should only use volunteers in cases where there is a definite advantage to doing so; volunteers shouldn’t be employed where a task can be performed satisfactorily by locals. Using volunteers can be particularly valuable when local skills are lacking. For instance, medical expertise and training is incredibly scarce in parts of rural Africa. Volunteers from abroad with these skills (such as medical students) can help meet acute needs. In these cases, volunteers should possess a willingness to pass on their skills, promoting self sufficiency in the long run. In providing free labour, volunteers might also enable projects that would be too costly or time consuming for communities to undertake themselves, with immediate subsistence being the primary preoccupation in many places. Charities should be transparent in their use of funds; as a volunteer you want to be sure that money you raise goes to the community and isn’t consumed as profit or administration costs. Charities should insist on volunteers being appropriately qualified and provide training where necessary; organisations should ensure volunteers are actually capable of meeting community needs. Organisations that work with vulnerable children should maintain high safe guarding standards.

Many organisations are responsible. Global Vision International is an example of an NGO supplying volunteering for a large number of projects, that specifies that projects must be instigated on community request. A smaller scale organisation Little Big Africa (LBA), based in Eastern Uganda also meets these criteria and has historically hosted volunteers from Oxford (including myself) via Oxford Development Abroad. Working for LBA, the emphasis was on empowering the community to take itself forward. As volunteers we spent nearly 2 months living in the village of Bushika in Uganda, which had requested LBA’s help. Upon arrival we met a man named James in his early 20s, who was unemployed. He asked if we could pay him to work for us during our stay, but unfortunately, this wasn’t possible. However, through one of LBA’s schemes, by the time we left James had found employment. In rural Uganda most people continue to cook on traditional open fires – due to fairly regular afternoon rain, this usually happens inside. Combined with poorly ventilated clay brick houses, this creates an incredibly smoky living environment. As a result, lung disease is a common affliction in rural Uganda (the subject of a 2015 study published in the Lancet). To tackle this, LBA uses volunteers to spread knowledge of how to build smokeless stoves. James was one of the individuals we trained whilst in Bushika, and he now intends to build these stoves as a business.

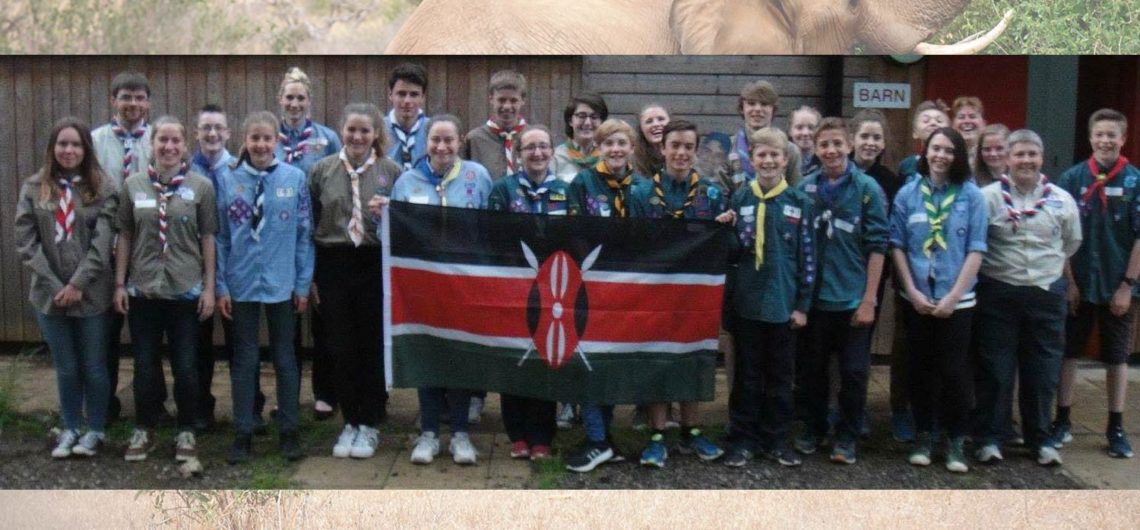

The Nasio Trust is another organisation that in the past has harnessed the efforts of volunteers from Oxford for good, focusing on improving the lives of vulnerable children. Nasio works in Western Kenya, in the communities of Mumias and Musanda, both of which are close to the main transit route between the Kenyan port of Mombasa, and landlocked Uganda. Because of the large number of haulage workers passing through the area, the area has historically had high levels of prostitution and HIV, leaving many children missing parents. Aware of the potential harm done by the institutionalisation of children, Nasio has developed a different model of support. Nasio facilitates the adoption of orphaned children by extended family members, and aims to support families with a single parent, to keep them together where possible. It does this by providing foster families with food, access to healthcare and education. It also seeks to tackle the problem of HIV at source by providing alternative means of income for the community; it has introduced farming of the valuable health food spirulina. The organization employs 49 people within Kenya; volunteers undergo a full orientation briefing upon arrival, and are given tasks that relate to their skills.

There are clearly responsible volunteering opportunities out there; it is the responsibility of prospective volunteers to search for them.